Plastic is everywhere from lunch boxes to takeout tubs. ♻️ But if you’ve heard Plastic Containers Are Toxic, the real question is: toxic how, under what conditions, and what’s a practical next step?

This guide breaks down the science in plain English, without hype, and helps you reduce risk while staying realistic about daily life.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- The phrase Plastic Containers Are Toxic is sometimes true – risk depends on plastic type, wear, and how you use it (heat, fat, time).

- Chemical migration into food can increase with microwaving, hot liquids, oil/fatty foods, and scratched containers.

- “BPA-free” is not a perfect safety guarantee; it’s better to focus on use habits and safer materials where it matters most.

- The easiest high-impact swap: store hot or acidic foods in glass or stainless steel whenever possible.

Note: This article is educational and does not replace medical advice. If you have health concerns, consult a qualified clinician.

Are Plastic Containers Are Toxic? A Clear Explanation

People say Plastic Containers Are Toxic because some plastics can release small amounts of chemicals into food especially under certain conditions (heat, abrasion, fatty foods). That doesn’t mean every plastic container is “poison,” and it doesn’t mean one exposure equals harm.

A more accurate way to think about it is risk management:

- Hazard: some chemicals used in plastics can interfere with hormones or cause irritation in lab settings.

- Exposure: whether those chemicals actually transfer into your food in meaningful amounts.

- Context: how often you use plastic, what you store, and how you heat it.

For official context on how food-contact materials are evaluated, see the FDA overview of food contact substances.

What “Toxic” Can Mean in Food Storage

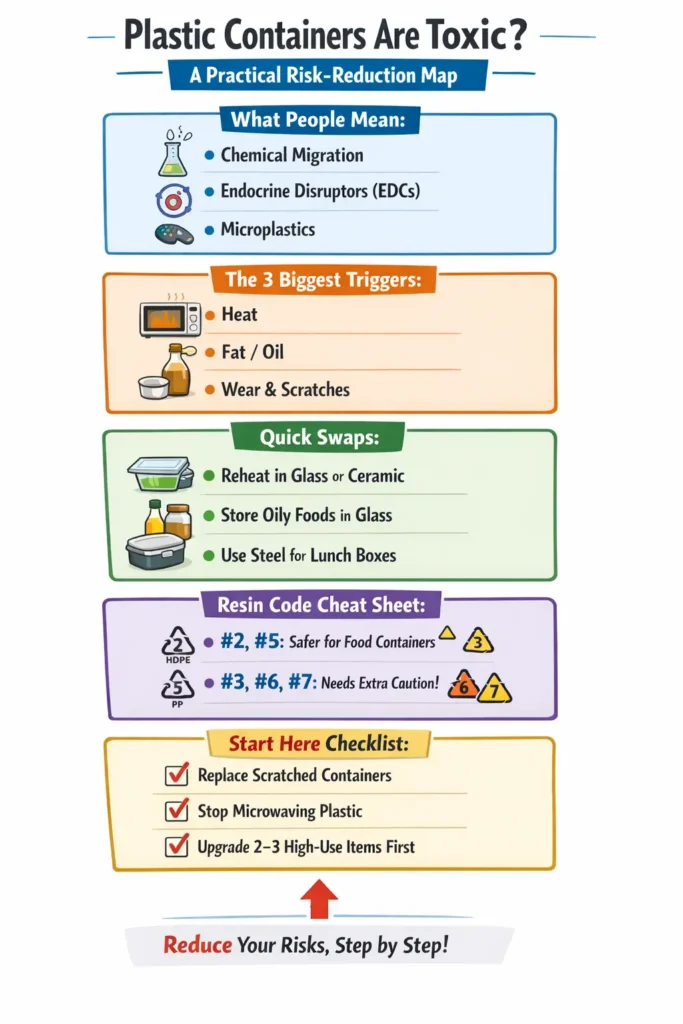

When headlines imply Plastic Containers Are Toxic, they often mix several issues together. Here are the main ones without sensationalism.

1) Chemical migration (“leaching”) into food

Some plastics may contain or be made with chemicals such as:

- Bisphenols (e.g., BPA in certain products historically)

- Phthalates (often associated with flexibility; more common in some plastics than others)

- Additives like stabilizers, colorants, and processing aids

Migration is influenced by temperature, food composition, and contact time.

For a science-based overview of BPA, NIEHS is a solid starting point.

2) Endocrine disruption (hormone-related pathways)

Some chemicals are discussed as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). This is a broad category; risk depends on dose, timing, and individual factors.

WHO has a helpful fact sheet.

3) Microplastics (a different – but related – topic)

Microplastics can come from many sources (packaging, textiles, environment). Food storage containers can contribute via wear and tear, but they’re not the only driver.

When Plastic Containers Become Higher-Risk

If you’re trying to respond intelligently to the claim Plastic Containers Are Toxic, focus on the situations that increase potential exposure.

Higher-risk use cases

- Microwaving in plastic (especially older plastics, stained plastics, or unknown plastics)

- Pouring boiling liquids into plastic containers

- Storing oily/fatty foods (e.g., curry, cheese sauces) for long periods

- Storing acidic foods (e.g., tomato sauce, citrus dressings) in worn containers

- Using scratched, cloudy, or warped containers (more surface area + more wear)

Lower-risk use cases (still not “perfect,” but better)

- Cold, dry foods (rice, oats, crackers)

- Short contact time (transporting, not long-term storing)

- Newer, intact containers used as directed

A practical rule: heat + plastic is the combination worth reducing first.

How to Decode Plastic Numbers (Resin Codes)

Resin codes (the numbers in the recycling triangle) are not a “toxicity score,” but they can help you make more informed choices.

| Resin Code | Common Plastic | Typical Uses | Practical Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | PET | Water bottles, some food packaging | Often single-use; not ideal to reuse repeatedly |

| #2 | HDPE | Milk jugs, some containers | Generally considered more stable for cold use |

| #3 | PVC | Wraps, pipes | Often avoided for food storage due to additives concerns |

| #4 | LDPE | Bags, wraps | Flexible; better for cold use than heat |

| #5 | PP | Many food containers, lids | Common “microwave-safe” plastic, but heat still increases migration potential |

| #6 | PS | Foam cups/containers | Often avoided for hot foods |

| #7 | Other | Mixed (polycarbonate, etc.) | “Other” is broad—harder to judge without details |

Step-by-Step: Reduce Exposure Without Panic

If your takeaway from Plastic Containers Are Toxic is “I need to throw everything away,” pause. The most sustainable path is targeted upgrades.

Step 1: Identify your “hot spots”

Look for where plastic contacts:

- Heat (microwave, dishwasher high heat cycles, hot leftovers)

- Oil/fat (rich foods, oily sauces)

- Acid (tomato, vinegar-based meals)

Start with one category (e.g., microwaving lunches).

Step 2: Replace the most-used items first

High-impact swaps:

- A glass container set for leftovers

- Stainless steel lunch box for daily use

- Silicone lids or stretch covers for bowls (for cold/room temp)

If you’re looking for eco alternatives to plastic, start with safer and long-lasting materials like wood, glass, and stainless steel.

Step 3: Keep plastic for the “low-risk” roles

Plastic can still be useful for:

- Dry pantry storage (if airtight)

- Outdoor travel where breakage is a concern

- Short-term cold storage

This is how you respond rationally when people say Plastic Containers Are Toxic—by using them more selectively.

Step 4: Use safer habits immediately (free upgrades)

- Let food cool before lidding and storing in plastic

- Don’t microwave plastic if you can use ceramic/glass instead

- Avoid scraping with metal utensils inside plastic containers

- Replace containers that are scratched, cloudy, or smell like old food

Step 5: Don’t get trapped by labels

“BPA-free” can be helpful, but it’s not a complete solution. The bigger win is still: reduce heat contact and use inert materials (glass/steel) for hot foods.

For safer product-selection tips, see EcoNir’s guide to BPA-free food storage: https://econir.com/bpa-free-food-storage

Quick Comparison: Plastic vs Glass vs Steel vs Silicone

| Option | Best For | Key Pros | Key Cons | Overall Practical Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic (PP/HDPE) | Cold + dry storage | Light, cheap, unbreakable | Heat can increase migration; scratches over time | Good (with limits) |

| Glass | Leftovers, reheating | Inert, easy to clean, oven/microwave friendly | Breakable, heavier | Excellent |

| Stainless steel | Lunch boxes, travel | Durable, lightweight, long lifespan | Not microwaveable; higher upfront cost | Excellent |

| Silicone (food-grade) | Lids, freezer, snack bags | Flexible, good for cold/freezer | Quality varies; can hold odors | Good |

| Ceramic | Reheating, serving | Inert, microwaveable | Heavy, can chip | Very good |

This table is the “action layer” behind the statement Plastic Containers Are Toxic: don’t treat all plastics equally, and don’t treat all use cases equally.

If you’re confused about material safety, read our detailed guide on Wood vs Plastic: Which Is Safer for Health?

Simple Chart (Example Data): Risk Triggers vs Exposure

Below is example data to visualize how usage patterns can influence relative exposure risk. (It’s not a lab measurement—just a practical model.)

| Scenario | Heat | Food Type | Container Condition | Relative Migration Risk (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold water in new bottle | Low | Watery | New | 1/10 |

| Overnight salad in plastic | Low | Mild acid/oil | Good | 3/10 |

| Hot soup poured into plastic | High | Watery | Good | 6/10 |

| Microwaving oily leftovers in plastic | High | Oily | Good | 7/10 |

| Microwaving in scratched plastic | High | Mixed | Scratched | 9/10 |

Mini Case Study: A “Mostly Plastic-Free” Kitchen in 30 Days

A realistic household goal isn’t “zero plastic overnight.” It’s reducing the scenarios most linked to the worry that Plastic Containers Are Toxic.

Starting point

- Family of 3

- Takeout 2×/week

- Microwaves lunch daily in plastic

- Uses old stained containers for leftovers

30-day plan (what worked)

- Week 1: Switch microwaving to glass (kept plastic for cold storage)

- Week 2: Stainless lunch box for weekday meals

- Week 3: Stop reusing takeout containers for reheating (still okay for cold transport)

- Week 4: Replace scratched containers; keep only intact plastic for pantry/dry foods

Result (practical, not perfect)

- Less plastic-heat contact (biggest win)

- Easier cleaning and fewer food odors

- Lower waste than “throw everything away,” because replacements were gradual

This is the balanced response to Plastic Containers Are Toxic: make the changes that matter most first.

Curious about the real results of a zero-waste lifestyle? We’ve shared practical case studies here.

Best Practices + Mistakes to Avoid

Best practices

- Prefer glass or steel for hot food storage and reheating

- If using plastic, choose intact, newer containers, and follow manufacturer instructions

- Use wood or silicone utensils inside plastic to reduce scratching

- Store tomato-based and oily foods in glass where possible

Common mistakes

- Reheating daily in old plastic because it says “microwave safe”

- Assuming “BPA-free” means “no chemical migration”

- Reusing single-use packaging for months

- Keeping containers that are stained, cracked, or smell strongly

When someone insists Plastic Containers Are Toxic, these habits are the calm, high-value upgrades that actually move the needle.

Tools & Resources

- Glass meal-prep containers with locking lids (choose tempered glass if available)

- Stainless steel lunch boxes (simple, durable; great for travel)

- Digital kitchen scale + batch-cooking routine (reduces takeout reliance—often more impactful than container choice)

- EPA Safer Choice for cleaning products that touch your dishes and storage.

- Background on global plastic pollution from UNEP.

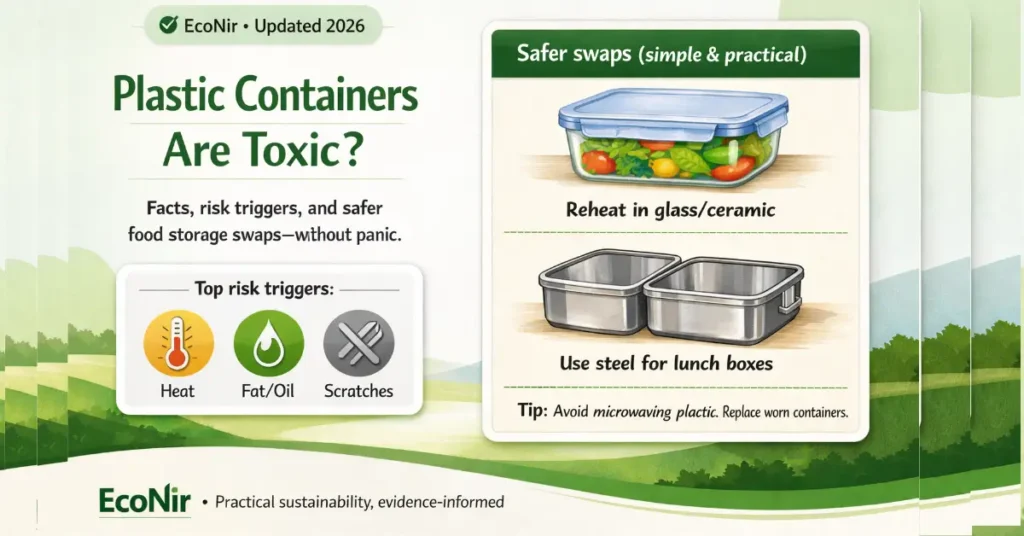

Many people worry about chemical migration, endocrine disruptors, and microplastics. This infographic shows the 3 biggest triggers (heat, oil, scratches), safer resin codes (#2, #5), and practical upgrades like switching to glass, ceramic, or stainless steel.

FAQs

1) Are plastic food containers safe for everyday use?

For many people, everyday use can be reasonable—especially for cold, dry foods and short storage times. The bigger concern is repeated exposure under conditions that increase migration: heat, oily foods, and scratched surfaces.

If you want a simple rule: use plastic for pantry items and cold storage, and prefer glass/steel for reheating and hot leftovers.

2) Is it true that microwaving plastic is dangerous?

Microwaving increases temperature and can increase chemical migration compared to cold use. Even if a container is labeled “microwave safe,” that typically refers to the container not melting or warping not a guarantee of zero migration.

A practical upgrade is to microwave food in glass or ceramic, then transfer if needed.

3) Does “BPA-free” mean non-toxic?

Not necessarily. “BPA-free” only tells you BPA wasn’t used (or is below certain thresholds). Other bisphenols or additives may still be present depending on the material and manufacturing.

Instead of relying on one label, reduce your highest exposure scenarios: hot + oily + plastic.

4) Which plastic types are safest for food storage?

No plastic is perfect, but HDPE (#2) and PP (#5) are commonly used for food storage and are often considered more stable for many everyday uses (especially cold storage).

The most important piece is still how you use it: avoid heat and replace damaged containers.

5) Are takeout plastic containers safe to reuse?

They’re often designed for single use, and repeated washing/heating can increase wear. Reusing them for cold transport (e.g., bringing snacks) is usually a lower-risk choice than reheating in them.

If you regularly get takeout, keep one or two for cold use and retire them once they scratch or warp.

6) Do scratched plastic containers leach more chemicals?

Scratches increase surface area and signal material wear, which can make migration more likely especially with heat and oils. Scratched containers also trap odors and residues, making cleaning harder.

A good rule is to replace plastic containers once they become cloudy, scratched, or permanently stained.

7) How can I reduce microplastics from food storage?

Focus on the easy wins:

Avoid heating food in plastic

Replace heavily worn containers

Prefer glass/steel for long storage of hot, acidic, or oily foods

Microplastics come from many sources, so container upgrades are helpful but not the only step.

8) What are the best alternatives to plastic containers for meal prep—and what do they cost?

Common alternatives:

Glass container sets: usually mid-priced; often last years if not dropped

Stainless steel lunch boxes: often higher upfront cost but extremely durable

Silicone bags: mid to higher cost; quality varies

Costs vary by region and brand, but the most cost-effective approach is to buy 2–4 high-use items first (for daily lunches and reheating) instead of replacing everything at once.

Next Steps Checklist

The phrase Plastic Containers Are Toxic is best treated as a context-dependent warning, not a blanket statement. Some plastics can migrate chemicals into food—especially with heat, oily foods, and wear—but you can lower exposure significantly with a few realistic changes.

Next steps (save this checklist)

- Stop microwaving food in plastic when possible

- Move hot leftovers into glass/ceramic

- Replace scratched, cloudy, or warped plastic containers

- Keep plastic mainly for cold/dry storage

- Upgrade one “hot spot” category first (lunches, soups, tomato sauces)